Last April, I received a letter from the Memorial Center in Moscow—an organization I contacted in hopes of tracking down additional information about my great-uncle Genek, who was deported from Poland in 1941, along with his wife Herta, to one of Stalin’s Siberian gulags.

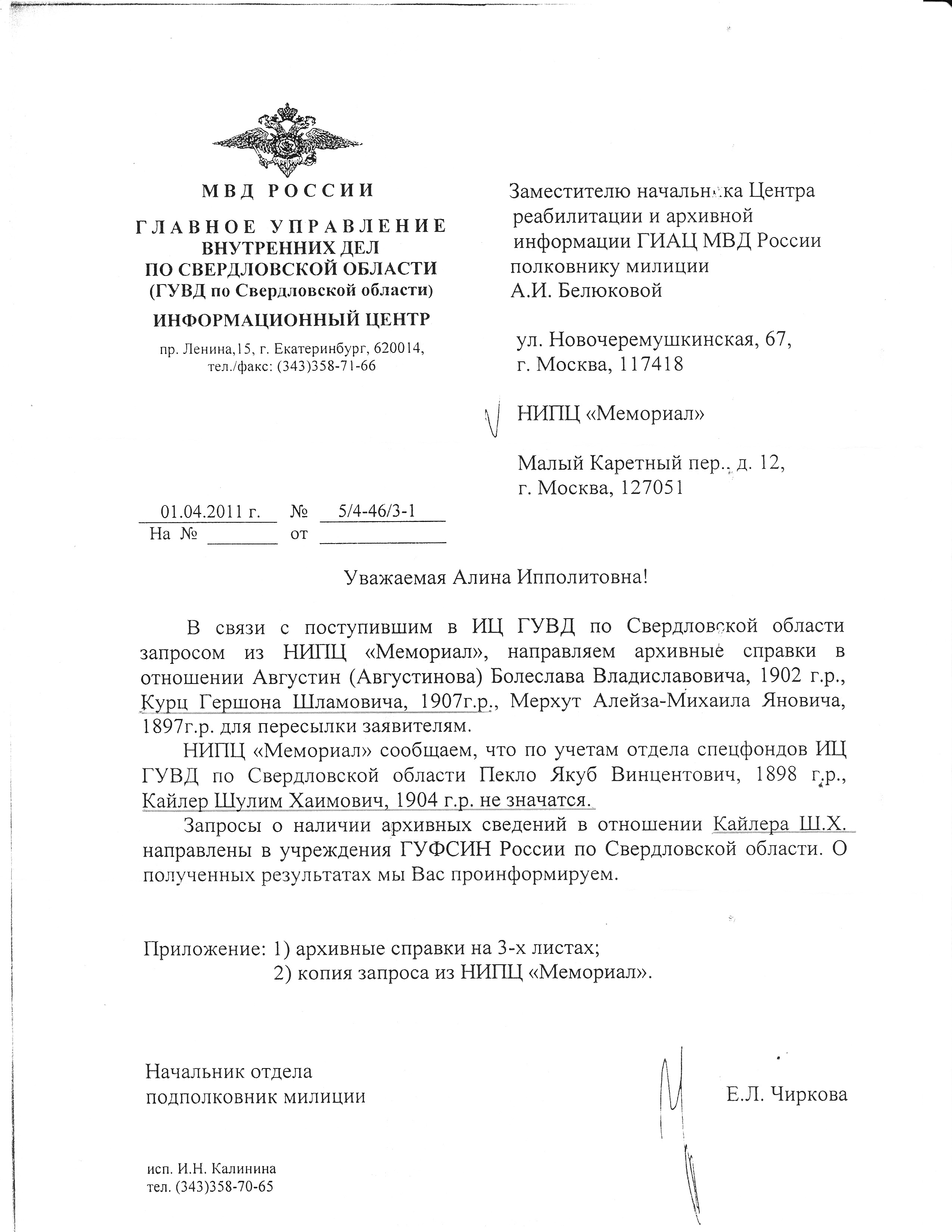

The letter I received from the Memorial Center in Moscow regarding records for my great-uncle, Genek

A woman by the name of Olga Cheriepova, a member of the Memorial Center’s Polish Committee, sent two responses to my inquiry, one written in Russian, and one in Polish. She’d found a record of Genek’s name, she said, and prompted me to contact the Ministry of Internal Affairs for details. What struck me the most about her letter wasn’t the fact that Genek’s records did, in fact, exist; it was her closing statement. It read:

As citizens of the country that was responsible for harm toward Poland and the Polish people, please accept our words of regret for the suffering and injustice sustained by your great-uncle Genek.

Immediately I followed up with my translator, to be sure she’d gotten the message right. Sure enough, 70 years later, Russia was apologizing.

The Memorial Center’s response (in Russian) to my inquiry, including an apology “for the suffering and injustice sustained by [my] great uncle, Genek.”

Apologies are interesting. Most, if delivered genuinely, offer a bit of consolation and, later on down the road, pave the way to forgiveness. But Cheriepova’s “words of regret”—70 years after the fact—felt to me like too little, too late. Genek and Herta were just two of countless innocent men, women and children plucked from their homes, herded into cattle cars and sent off to forced labor camps in the far reaches of Siberia (in her book,

Gulag, Anne Applebaum estimates that the USSR forced a total of

28.7 million laborers into the gulag system from 1930-1953). Does “we’re sorry” really cut it?

After reading Cheriepova’s letter, my mind immediately leapt to Hitler. What about the 6,000,000 souls lost to the Holocaust? Did their families ever receive an apology? It turns out some did.

President François Hollande gave a speech this summer in which he admitted that France was responsible for the death of thousands of Jews residing in France during WWII. His speech was delivered on the 70th anniversary of a two-day police roundup of more than 13,000 Jews in Paris in July of 1942. (The story of the Vel d’Hiv roundup is told in Sarah’s Key, based on the novel by Tatiana de Rosnay.)

French President François Hollande shakes hands with veterans at a Jewish memorial during ceremonies to mark the commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the Vel d’Hiv roundup

While apologies such as Hollande’s and Cheriepova’s will never, of course, make up for what happened, they are, I suppose, a step in the right direction. To admit fault is a brave and difficult thing, especially when it comes to personal (and in this case, national) pride.

I wonder often what Genek and Herta would have thought of Ms. Cheriepova’s letter. I’ve been told they rarely spoke of Siberia—their time in the gulag, it seems, was a chapter of their lives they preferred to forget. Perhaps they’d have shrugged the apology off with an attitude of what’s done is done. Or perhaps they’d have felt worse, the words a reminder of the frigid winter they spent felling logs, listening to the howl of wolves through the thin walls of their barracks. Or perhaps, over time, they’d have accepted the apology, and a small piece of their conscience would rest easier, knowing the wrongs they’d endured had been recognized. I guess we’ll never know.