It’s official–the holidays are upon us. This evening, families will gather to light the first of their menorah candles, hosts will begin prepping their holiday menus and children will sit down in pine-scented homes to pen letters to the North Pole. In the midst of it all, I can’t help but reflect on my own holiday rituals, and on those of my ancestors. What was it like, I wonder, to watch the holidays come and go as a Polish Jew during the Holocaust? Let’s try to imagine. Join me, if you will, as we step back in time 72 years, to the war-torn world of my grandfather and his siblings.

The date: December 8th, 1940.

Your country no longer exists. The Polish army, which put up a gallant fight at the start of the war, has surrendered. Germany occupies the western half of Poland; Russia occupies the east. (Poles, however, continue to fight abroad alongside the Allies under a British government-in-exile.)

A young Jewish boy sells armbands in Radom, Poland, 1940

Your hometown of Radom is under German control. The city’s ~30,000 Jews (a third of the population), are forced to wear white armbands with blue stars; getting caught without one is punishable by death. Jewish schools are closed, Jewish businesses have been confiscated, a strict curfew is established. There is talk amongst the Schutztaffel of constructing a ghetto.

Your family’s fabric shop has been sequestered. Food rations have dropped to an all-time low. Your mother is put to work in a cafeteria peeling potatoes for the Gestapo; whenever she dares, she sneaks a handful of peelings home to make broth. Your sister Halina works at a farm outside Radom. The produce she harvests feeds the German military; her pay is a bit of bread.

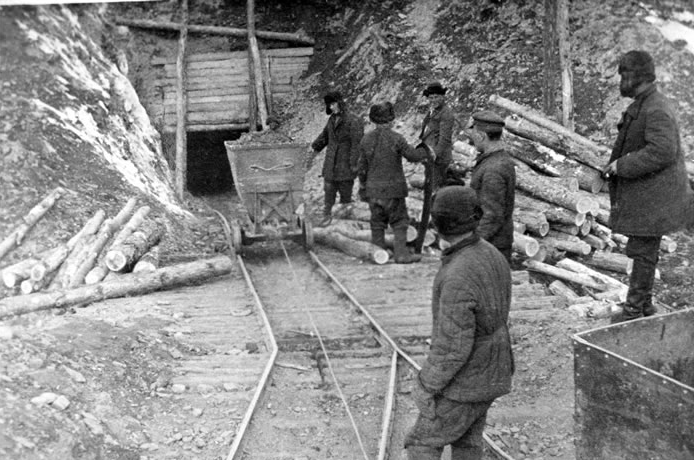

Prisoners mine gold at Kolyma, the most notorious Gulag camp in extreme northeastern Siberia. Courtesy of the Central Russian Film and Photo Archive.

Your brother Jakob lives in Lvov and works at a factory mending Russian uniforms from the front. Your sister Mila hasn’t heard from her husband in over a year, ever since he was called up to join the Polish army. She works at a uniform factory in Radom. Her daughter Felicia, two years old, comes to work with her every day, where she spends hours alone, in hiding.

Your brother Genek and his wife Herta have nearly frozen to death within the confines of their Siberian gulag. Herta is nine months pregnant. She must continue working until the baby comes–the rule, “To eat, you must work,” makes no exception for pregnant women.

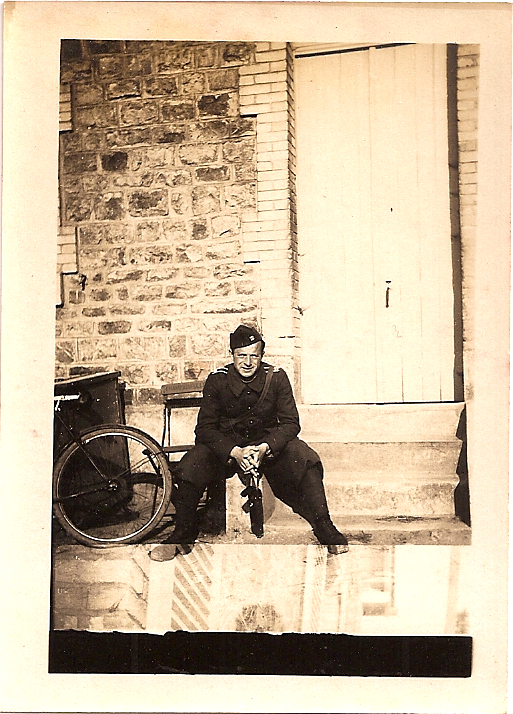

Less than a year after enlisting in a Polish column of the French Army, Addy forges his demobilization papers and hitchhikes south toward Marseille, on a dogged mission to get out of Europe.

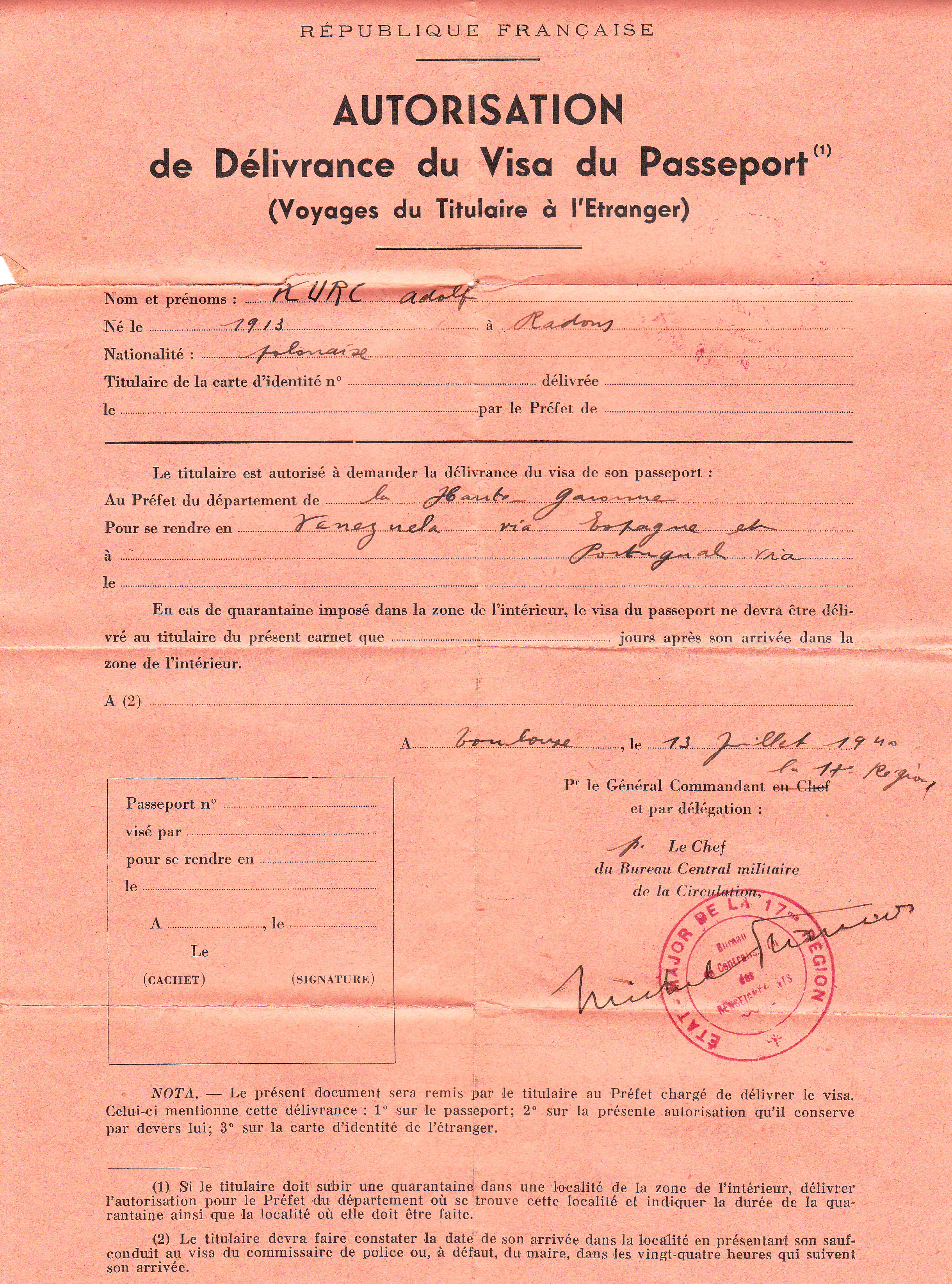

You are in the process of gathering the paperwork you need to leave Nazi-occupied France. You’ve been denied visas to Venezuela, Argentina and America. You are now in Vichy, where you’ve been denied a Brazilian visa as well. Rather than give up, you decide you’ll wait outside the embassy to speak with the ambassador in person. Can you charm your way to a visa–and out of Europe? You have nothing to lose.

The paperwork documenting Addy’s request for a Venezuelan visa. His request is denied.

Fast forward six years and the Holocaust has taken its toll. Of Radom’s 30,000 Jews, fewer than 300 survive. The Kurcs, incredibly, comprise nearly seven percent of the city’s total survivors.

Fast forward another two-thirds of a century, and here I am, at the keys of my computer. I am a click away from virtually anything–a plane ticket, a doctor’s appointment, a video chat with my grandmother. My son naps in the room next to me, curled up with a stuffed zebra, surrounded by photos of his family. After we put him to bed tonight, my husband and I will enjoy a quiet dinner and a glass of wine by the fire. Small luxuries, but luxuries indeed.

Wyatt celebrated his first birthday and Thanksgiving alongside his parents, grandparents and aunt and uncle on Martha’s Vineyard.

This holiday season, I am grateful. I’m grateful for my boys, whose smiles make me feel warm inside. I’m grateful for the roof over our heads that stood up to the wrath of Hurricane Sandy, and for the friends who took us in when we were without power for a week. I’m grateful for our health, our safety, our freedom–for the things I’m reminded over and over again in my research that I must never take for granted.

I am grateful of course for the Kurcs, whose story has instilled in me the belief that with courage, perseverance, ingenuity and a bit of luck, nearly anything is possible.

Finally, I am grateful for you! My family, friends and followers–for your support as I continue along this journey. I couldn’t do it without you. I wish you all barrels of cheer this holiday season–I look forward to turning the page together in 2013.